Two-wheeled micromobility options, especially e-kickscooters and electric cargo bikes, have become very popular in cities. Three- and four-wheeled minimobility may be the next big thing.

Today’s micromobility landscape is primarily defined by electric bicycles, mopeds, and ekickscooters. Below the surface, however, another mobility segment with similarly impressive growth rates has recently gained traction: three- and four-wheeled minimobility. This segment, which falls between cars and bicycles, includes threeor four-wheeled electric vehicles (EVs) that fit one to two persons. These vehicles have an average weight between 100 and 500 kilograms when unoccupied. Depending on the vehicle type and local regulations, their maximum speed varies from 25 to 90 kilometers per hour.

Because of their smaller size, minimobility vehicles are less expensive than standard EVs, consume less space, and have more parking options—characteristics that are especially beneficial in crowded urban areas.

Other advantages include the following:

1. Minimobility vehicles require fewer resources and energy during production; this is especially helpful considering that some resources, such as battery components, are already in short supply.

2. Energy requirements for minimobility-vehicle operation are lower than those for standard EVs; this is important because many regions, including the European Union, will not be able to produce enough green energy at the local level for decades.

3. Minimobility vehicles increase safety because they usually travel more slowly and are more visible to pedestrians and bikers. Compared with other micromobility options, such as e-kickscooters, bicycles, and mopeds, minimobility vehicles offer greater convenience and comfort, including the ability to sit and better protection from the weather. Further, they offer extended storage space and a capacity of two passengers.

If interest in minimobility rises, and if regulators push this mobility option, this segment could reach a total addressable market of $100 billion annually across China, Europe, and North America by 2030. (For perspective, the two current leading manufacturers of two-wheeled EVs have generated a cumulative $300 million in global revenues from this segment since

2015.)

To gain more insight into this growing market, the McKinsey Center for Future Mobility surveyed 26,000 people in eight countries about their views on minimobility vehicles, including their willingness to purchase a vehicle in this class. The survey also assessed whether the growth of minimobility vehicles could affect car ownership rates or shift mobility preferences. The survey is part of the Mobility Consumer Insights survey series, which focuses on exploring future trends.

The micromobility wave

The growth of minimobility is in line with the uptick in micromobility options, including ekickscooters, bicycles, and mopeds, over the past few years. Like minimobility vehicles, these small transport options provide a greener, less expensive mobility alternative, especially for short trips.

Today, most minimobility options are privately owned. Shared ownership is most common in the European Union, especially in France. Adoption rates for minimobility vehicles are highest in China, which has long been a hotbed of micromobility. In the United States, golf cart–like vehicles—some of which exceed our weight definition—are almost always privately owned and are often called neighborhood electric vehicles.

The minimobility market

More than 30 percent of respondents worldwide state that they are likely or very likely to consider using a minimobility vehicle as one of their future mobility options—but location had a big impact on opinions (exhibit). Respondents from Brazil and China are most likely to consider these vehicles (more than 50 percent) followed by those in Italy, Japan, South Korea, and the United States (between 25 and 30 percent).

Consideration rates are lowest in Australia and Germany (15 to 20 percent). These findings show that willingness to use minimobility is highest in countries, such as China, with a long tradition of small-sized vehicles. It is lowest in countries such as Australia and Germany, where large cars are popular.

While minimobility appealed to many different consumer segments, distinct patterns emerged. For instance, about 90 percent of the respondents who were willing to consider these vehicles live in urban and suburban areas, and only about 10 percent lived in rural areas. These findings may reflect the fact that urban and suburban residents tend to drive shorter distances that fit within the range of minimobility vehicles. They may also prefer vehicles that can fit in smaller parking spaces than traditional cars.

When we divided the share of respondents who are willing to consider a minimobility option by income, we found that a majority— about 58 percent—have a low to medium salary (less than $50,000 annually). These respondents may be more receptive to minimobility because of their lower price point compared with traditional cars. The relatively low cost of minimobility may increase EV ownership rates among people who might otherwise purchase traditional combustion vehicles, which generally cost less than EVs. Other trends noted in the survey among respondents who are willing to consider a minimobility vehicle include the following:

1. About 35 percent currently own a premium car; 31 percent own a car in the entry and volume segment.

2. More than 60 percent live in a single-car household, 29 percent in a multicar household, and 10 percent in households without cars.

3. Willingness to consider a minimobility vehicle varies by agegroup; it is 20 percent for respondents between the ages of 18 and 29, 46 percent for those between 30 and 49, 24 percent for those between 50 and 64, and only about 10 percent for those aged 65 and older.

4. Consumers enthusiastic about electromobility are also more likely to consider minimobility vehicles. In our survey, EV owners are almost twice as likely to consider a purchase compared to non-EV owners, and consumers with a concrete plan to purchase an EV are twice as likely to consider a minimobility option.

The survey asked respondents specifically if they would consider replacing their private vehicle with a minimobility vehicle over the long term. Overall, 35 percent of those who were willing to consider a minimobility vehicle are willing to take that step. A higher percentage (more than 50 percent) are willing to purchase a minimobility vehicle and use it in addition to their current vehicles—in other words, an extension of their current transportation options rather than a complete replacement.

As with any transportation option, minimobility vehicles can serve multiple purposes. When we asked respondents about their main use for these vehicles, most say grocery shopping (48 percent), followed by leisure activities (36 percent) and commuting (31 percent). Again, results vary by location. For example, American and Chinese respondents are less likely than other respondents to cite grocery shopping as the main use case (both about 12 percent below the global average).

Implications for mobility stakeholders

Based on the survey results, we believe that minimobility vehicles are a viable extension to the current light-micromobility-vehicle landscape. Their growing popularity will raise important issues for different stakeholders, however, including the following:

1. City leaders: In urban areas, minimobility may emerge as a viable alternative, bringing the added benefits of decreased congestion, reduced space requirements, and lower emissions. Their advantages over other micromobility offerings, especially greater safety and weather protection, could be a major draw, as could their lower price, compared with standard vehicles. To increase the number of people who can benefit from minimobility vehicles, municipalities might deploy them as white-label car-sharing solutions, in which they obtain vehicles from private manufacturers or providers but brand them as their own. The offerings could be available for rent across the city and benefit a diverse population.

2. Micromobility service providers: Overall, minimobility options could be an important extension to the current vehicle portfolio at service providers because they allow riders to take trips or run errands that might be difficult with ekickscooters, bicycles, or mopeds— shopping for large items, for instance, or traveling during heavy rain. Furthermore, given their lower price points, minimobility options may represent profitable alternatives to today’s car-sharing vehicles. They might be especially important in small and medium-size cities, which are often unattractive markets for established micromobility players.

3. Vehicle manufacturers: In many cases, minimobility vehicles could become an important extension of a manufacturer’s brand, regardless of whether it is a car OEM or OEM, providing a new growth area. The contribution of minimobility vehicles to overall revenues may become more significant in the future as more cities begin to ban traditional cars in favor of smaller electric-mobility options.

4. New players: With a fast-growing market and limited technologic complexity, minimobility solutions may provide an entry opportunity for new players.

The interest in minimobility options is rising, and industry stakeholders can help encourage market growth through greater collaboration and joint commitments. Some city leaders might consider implementing regulations that promote the uptake of minimobility, for instance, or they might think about launching marketing campaigns that increase awareness. Likewise, OEMs could help by committing to increased production of minimobility vehicles to ensure that supply meets demand. For their part, mobility service providers could consider adding significant numbers of minimobility options to their fleets. With such crossindustry efforts, minimobility vehicles could provide greater convenience for urban residents, as well as a greener transport option to help in the battle against climate change.

The Center for Future Mobility’s mission is to help companies, investors, governments, and social sector entities transform the way they approach mobility in all its forms—making it easier, more sustainable, smarter, and cheaper for everyone.

How the pandemic has reshaped micromobility investments

After a one-year slowdown in 2020, capital is again flowing to micromobility. But the latest data show that new regions, vehicles, and investor types now dominate.

Co-leads the McKinsey Center for Future Mobility and serves clients across the automotive industry, incumbent industries, mobility disruptors and investors By Benedikt Kloss Driving future ground mobility and advanced air mobility topics with organizations across the whole mobility ecosystem By Timo Möller Co-leads the McKinsey Center for Future Mobility, focusing on disruptive trends such as vehicle connectivity, autonomous driving, electrification, and shared mobility By Darius Scurtu Co-leads McKinsey’s micromobility initiative and serves clients across the entire mobility ecosystem, providing data-driven insights August 3, 2022 ‑ Before the COVID-19 pandemic, investments in the sharedmicromobility industry soared in line with growing ridership and utilization. From 2015 to 2019, almost $7 billion was invested in this market. Funding contracted sharply in 2020, to around $800 million, but the industry is now resuming its growth trajectory, as we projected in a previous article, and capital flows are also rising. In 2021, micromobility players attracted approximately $2.9 billion in new investment, and they may exceed this level in 2022. But the capital flows are now coming from different types of investors, and they are going to regions and vehicle types different from those of the past.

To gain more insight into these differences, we used McKinsey’s Micromobility Investment Database, which applies big data algorithms to track publicly disclosed investments in companies that either provide shared-micromobility services or produce vehicles and supporting technology for the shared-micromobility industry. The tool can analyze investments by investor and by vehicle type—for instance, ekickscooters, electric bicycles, and electric mopeds—as well as geographic areas. It focuses on investment in companies in the core micromobility markets of Asia, Europe, and North America.

A regional shift to Europe

Since 2018, about $8.4 billion has been invested in micromobility companies in the three core markets—split relatively equally among Asia ($3.1 billion, or 37 percent), North America ($2.9 billion, 34 percent), and Europe ($2.4 billion, 29 percent)

To determine if funding patterns changed over time, we segmented total investment by looking at two time periods: the years before the pandemic (2018 to 2019) and the next three years (2020 to 2022). Our analysis shows that the flow of funds has not been evenly split in recent years and that Europe has taken the lead from Asia. Investments in micromobility companies headquartered in Europe represented only 12 percent of global flows before the pandemic but almost 50 percent from 2020 to 2022. Investments in North American companies also increased during the second time period. Asia had the most significant funding drop over time: from $2.7 billion (60 percent of the total) to just $400 million (10 percent).

One reason for this shift may be the accelerated measures (such as building dedicated urban bicycle and scooter lanes) that European policy makers have used to make micromobility safer and more attractive. In addition, many European players have grown extremely rapidly in recent years and are acquiring smaller competitors, thus fueling continued investment.

E-kickscooters remain the most prevalent vehicle type

Around the world, companies that focused on shared e-kickscooters attracted the most investment—$5.2 billion—from 2018 through 2022, followed by bicycles at $3 billion and mopeds at $200 million (both including electric offerings). Since the pandemic began, the share of investment going to e-kickscooters has increased and now stands at nearly 90 percent. That concentrated flow probably results from continued consolidation among ekickscooter providers as market leaders acquire smaller players

Splitting investments by region and vehicle type shows that e-kickscooters attracted 98 percent of total funding in North America and 86 percent in Europe from 2018 to 2022. By contrast, in Asia bicycles attracted the most investment—more than 80 percent of the total.

Another insight emerged through a deep dive on investments in companies that focus on providing supporting services for shared micromobility rather than offering the shared services by themselves. The analysis focused on start-ups that provide services related to parking, charging, fleet management, maintenance, and relocation.

Before the pandemic, investors had provided around $100 million in funding to such companies in China, Europe, and North America. This number more than tripled between 2020 and 2022, when it reached almost $350 million. A large portion of this increase relates to parking and charging solutions, which accounted for almost half of total investment, compared with only about 10 percent prepandemic. This strong growth may have occurred because it has become increasingly obvious that an efficient parking and charging infrastructure can reduce both operational costs and idle time for vehicles.

Such benefits are particularly important for free-floating, shared micromobility fleets.

Institutional investors continue to dominate the market

Investors fall into three main types:institutional investors, including banks, venture capitalists, and private-equity firms

OEMs (including those for micromobility) and suppliers mobility service providers

From 2018 through 2022, institutional investors have provided around $7.7 billion in micromobility funding—92 percent of the total $8.4 billion received. Mobility service providers accounted for about $500 million in funding, or 6 percent, and OEMs for about $170 million, or 2 percent

In the pandemic’s wake, institutional investors still represent the largest share of capital, but the gap has narrowed and the amount they invest has declined in absolute terms: they accounted for about $4.2 billion in funding from 2018 to 2019 but for only $3.4 billion from 2020 to 2022. For the same time periods, the amount mobility players invested nearly tripled, to $390 million, from $140 million.

Several trends help explain the investment shift. Before the pandemic, many venture capital firms invested in immature micromobility players, most likely because they saw the potential of this nascent market. More recently, larger sharedmobility players have been increasing their efforts to access the micromobility segment via mergers and acquisitions, thus raising their share of investment. In addition, existing micromobility players are investing more funds in their businesses as they expand into new cities or double down on new vehicle platforms or customer segments in the cities where they currently operate.

Institutional investors still preferred electricbicycle ventures in 2018, directing about 72 percent of their funding to this segment.

Their preferences began to change in 2019, however, when the buzz around ekickscooters started to accelerate. The share of institutional investment going to this segment rose from about 60 percent in

2019 to nearly 90 percent in 2021. Electric mopeds have attracted only minor interest from institutional investors across the years.

McKinsey data show that micromobility investment patterns have changed since the pandemic, with more funding now flowing to Europe and e-kickscooters. Institutional investors still provide the most funding, but their share has decreased. The micromobility segment will continue to evolve quickly, and we will continue to monitor developments.

More Stories

AUO Returning to CES Showcase Next Generation Smart Cockpit 2025

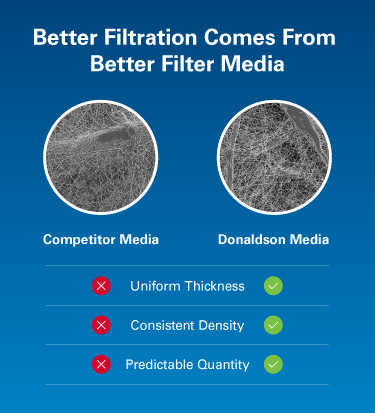

Donaldson Ultra-Web technology aims to set the standard in industrial filtration for cleaner air and cost-savings

Hydrogen’s Role in Decarbonising Sports and Entertainment Events