Some time back we looked at the increasing use of long-term warranties by vehicle manufacturers as a means of improving customer retention rates for their dealerships. The trend is continuing, with the addition of contractual service packages which lock customers in to using dealers.

Compounding the issue is greater complexity in vehicle design. Customer retention rates at main dealers for the repair and maintenance of the Toyota Prius is understood to be 20% higher than for Toyota’s “conventional” fleet. This is largely due to the complexity of the Prius, and consumer fears that independent garages cannot service their vehicles.

This is part of a worrying trend for independent garages throughout the industry, and we are seeing common themes emerging. In Europe pressure to keep business competitive has led to a myriad of initiatives – including the block exemption rules (BER). However, as this hasn’t proved to be the panacea that the EU or independent aftermarket had hoped for, initiatives such as the “Right to Repair” (R2RC) campaign are now lobbying for the right of the general public to chose the repair centre they wish – and the right of the independent aftermarket to safeguard its future through access to technical information, diagnostic tools, spare parts and, critically, training. The situation is typified by events taking place in the UK. At Datamonitor, we estimate that 31% of aftermarket trade is carried out by independent garages. Furthermore, the average age of a vehicle in the UK is 6.7 years. But, this channel is declining in the face of a steady rise in car ownership.

Many workshops run the risk of closure by the time the “R2RC” campaign bears fruit. What they do have in their favour is EU regulation 715/2007/EC, there are still limitations. Many all-make traders either cannot afford – or are put off by – the large investments that are required to acquire the tools, skills and training to diagnose and repair modern motor vehicles. Independent repairers which have invested find themselves acting as hubs for “traditional” garages, being sub-contracted to carry out work that others do not have the equipment or knowledge to do.

The question then is how does the independent aftermarket garage network survive and, crucially, safeguard the consumers’ right to choose. The answer, I suspect, lies in independent garage networks. Only large networks will have the financial muscle to stay in step with the market. They are ideally placed to evolve into chains or franchises. The standardisation and uniform presentation of garage networks gives another vital dimension – credibility, and the power of a brand. In the information-age, “word of mouth” is no longer sufficient for the majority. The absence of a website or evidence of capability or customer satisfaction will have a potential client looking for an independent elsewhere, or gravitating back to the main dealer – which, ironically, is not always a guaranteed location for such traits.

For smaller independents there is also an option for them which allow continuation of independence whilst voluntarily positioning themselves under the wing of a larger organisation and benefiting from the security that such a move can bring. The principle makes a lot of sense considering the difficulties that many independents face. To remain competitive either pay for tooling and education independently, or enter into a contract with a large wholesaler, an international trade group or a global parts manufacturer and convert your business to a franchised subsidiary that allows you to retain relative autonomy, whilst gaining access to preferential supply chains and, critically, the training, equipment and branding that can open the door to a wider customer base.

We see these trends across Europe – and also, interestingly, China. The tidal wave of vehicles that has entered the Chinese market over the last 5-10 years has resulted in significant re-organisation of the aftermarket. An example of this is Bosch’s service concept set up in China in 2001. By 2004, 310 garages were in operation, and by 2013 Bosch aims to have over 1,300 service centres across China. It is understandable to see why. Independent service centres, once the majority stakeholders of the Chinese aftermarket, have collapsed in market share suffering at the hands of “4S” manufacturer dealerships which now control approximately 50% of the aftermarket and, significantly, large-scale independent chains. Independents such as “Cinep”, “Autobacs” and “Bosch Car Service” are thought to hold approximately 25-30%.

Overall I anticipate a similar evolution will be seen in India over the coming years, as with the other emerging economies, as the independent aftermarket wakes up to the realisation that together we stand, and divided we fall.

More Stories

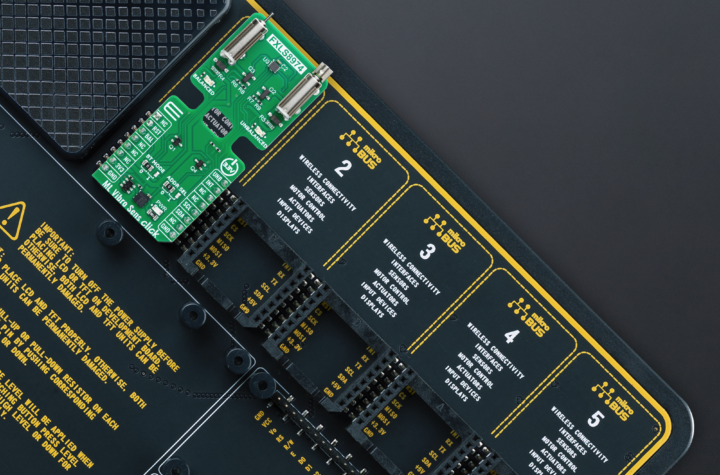

Mosaic Click board from MIKROE delivers global coverage multi-band and multi-constellation tracking ability

Current transducer from Danisense selected for DC charging station testing device demonstrator at TU Graz

New Click board from MIKROE helps develop and train ML models for vibration analysis